As part of our Black History Month programming, California Film Institute is spotlighting four local Black filmmakers we think our community should know about. We have invited these filmmakers to write an essay responding to our theme, “Celebrating Black creativity in cinema”, and reflecting on what inspires them to create. Throughout February, we will publish a weekly essay from this series.

This week we hear from Celia C. Peters, a filmmaker creating daring futurist stories about intriguing, authentic characters. She’s currently developing her afrofuturist feature film GODSPEED in partnership with the 150 Artist Studio at Warner Bros. Discovery. In 2022, she launched her afrofuturist audio drama DOMESTICATED. Peters was also named a 2022 Cultural Strategist in Government for the City of Oakland at the African American Museum and Library of Oakland; in this role, she is reimagining Oakland’s Black history using digital and immersive media. She curated Blackness Revisualized, the inaugural afrofuturist film festival presented by WNET-NYC/AllArts.org. She’s also director of Shutdown, a historical documentary produced by Ohio State University, currently in post-production. Peters is an Advisor to Sundance Co//ab screenwriting courses and her own work has screened in Los Angeles, NYC, Berlin, Washington, D.C., Detroit, Cleveland and London, plus public and cable television. She’s produced content for Afropunk, New York Comic Con and L.A.’s California African American Museum. Peters has an honors B.A. in French and Political Science from University Michigan and an M.A. in Public Policy from the University of Chicago, with graduate studies in clinical psychology at NYU.

Celia Peters Reflects on Black Creativity in Cinema

Very often, what inspires me to create is something I see — an image, a piece of art or a design; a person I come across: or something I hear, music, a conversation. The other thing that inspires me is science and metaphysics: an article, an event, a theory. What all of these have in common is that they are a snippet of something that I build a story around. With my current feature film project, GODSPEED (which is an afrofuturist sci-fi thriller), I was inspired by something I saw but did not understand. In the early 2000s, I lived in NYC. One Sunday afternoon, I was walking in my Harlem neighborhood when I passed an open door in what used to be some sort of commercial building. I heard music coming out….and was intrigued. I peeked in and saw what looked like a church service going on. (While I lived in the Big Apple, I had a habit of going into houses of worship if they were open….just to sit, be still, meditate, listen and connect.) So I went in. And I was not prepared for what I saw. There was a worship service happening in what looked like a former bank lobby. And as I recall, no pulpit per se, no minister or sermon. It was a packed house filled with music and people sitting in make-shift pews. The worshippers were a mixed bag racially, in age and style-wise…some even looked like tourists. But what caught my eye were two school-age children, a girl and boy dressed in church clothes, who were facing a side wall in the front of the space. Their bodies were stiff with arms outstretched toward the ground. Their eyes were closed and they were chanting at top speed. Although from where I sat in the back, I could not hear them. Their adorable faces were peaceful and enraptured….so I knew this wasn’t punishment. But what WAS happening? I left still not knowing. There was so much energy in the room and this mysterious moment felt pivotal. My mind and my spirit were inspired…and a story was born.

As a storyteller, I’m quite excited about the way technology is broadening the possibilities for contemporary cinema. Storytelling is an ancient aspect of human civilization, but the ways we are able to tell stories is expanding and growing to meet the multidimensional nature of the human mind. I’m excited about being able to create immersive cinematic experiences that tap into all of our senses. I’m especially thrilled by this because my particular approach to filmmaking, my auteurship, is rooted in classic cinema — especially film noir. Artistically, letting the story unfold and the ability to focus on and sit with characters is everything; it speaks to the psychology of character driven work. For me, there is real magic where new technology and vintage approaches meet.

At the same time, contemporary Black cinema excites me very much because we are finally seeing a kaleidoscope of voices and perspectives in film that approximates the diversity within the Black community. All of these cinematic voices represent the multifaceted, multidimensional reality that is Blackness. I am nurtured, energized and given life by seeing people who look, sound and/or feel like me on the screen — and more broadly, as a filmmaker, I am heartened, because the more threads in the fabric, the richer the tapestry is for all. Inclusion of everyone serves all who love film.

Black creativity is Black freedom. The freedom to tell stories of Black culture, whichever way that makes sense to you. The freedom to represent Black characters and stories that resonate with YOU. The name of my production company is Artistic Freedom, because that’s what it’s all about for me. I, a Black woman artist, am free to create whatever, however, whenever, whyever I want. I choose to lead with that and I want everyone who encounters my work to understand that. As an artist, I want to make people feel, I want to make them think and ultimately, I want to elevate the human condition with my work. What I do may make some uncomfortable… but that comes with the territory of creativity and of growth.

The role of the Black filmmaker and artist in society is to show up and create. Show up and tell stories. Show up and be our actual creative selves. My hope would be that we do so in the most authentic ways possible, but I am loathe to put any limits on us. If you choose to be a Stepin’ Fetchit, that’s your choice. And because I believe in artistic freedom, I think Black creatives should be free to make that choice. Personally, I despise coonery, so I make things in the opposite direction. But I don’t want to dictate other people’s lanes. That said, rest assured, I also wholeheartedly believe in the right to call out garbage if one sees garbage. Black filmmakers and artists have a right to have an opinion. I do not and will not support work or art that I feel is destructive to Black people or women (or any other group — it’s not my thing). The American film industry has a legacy of putting Black people working within it at odds with themselves. Even if you need a job, the choice to participate in the denigration, distortion or existential oppression of your own is just that: a choice that has consequences. If you think the only way you can support yourself is by doing work that denigrates who you are, I encourage you to ask yourself why.

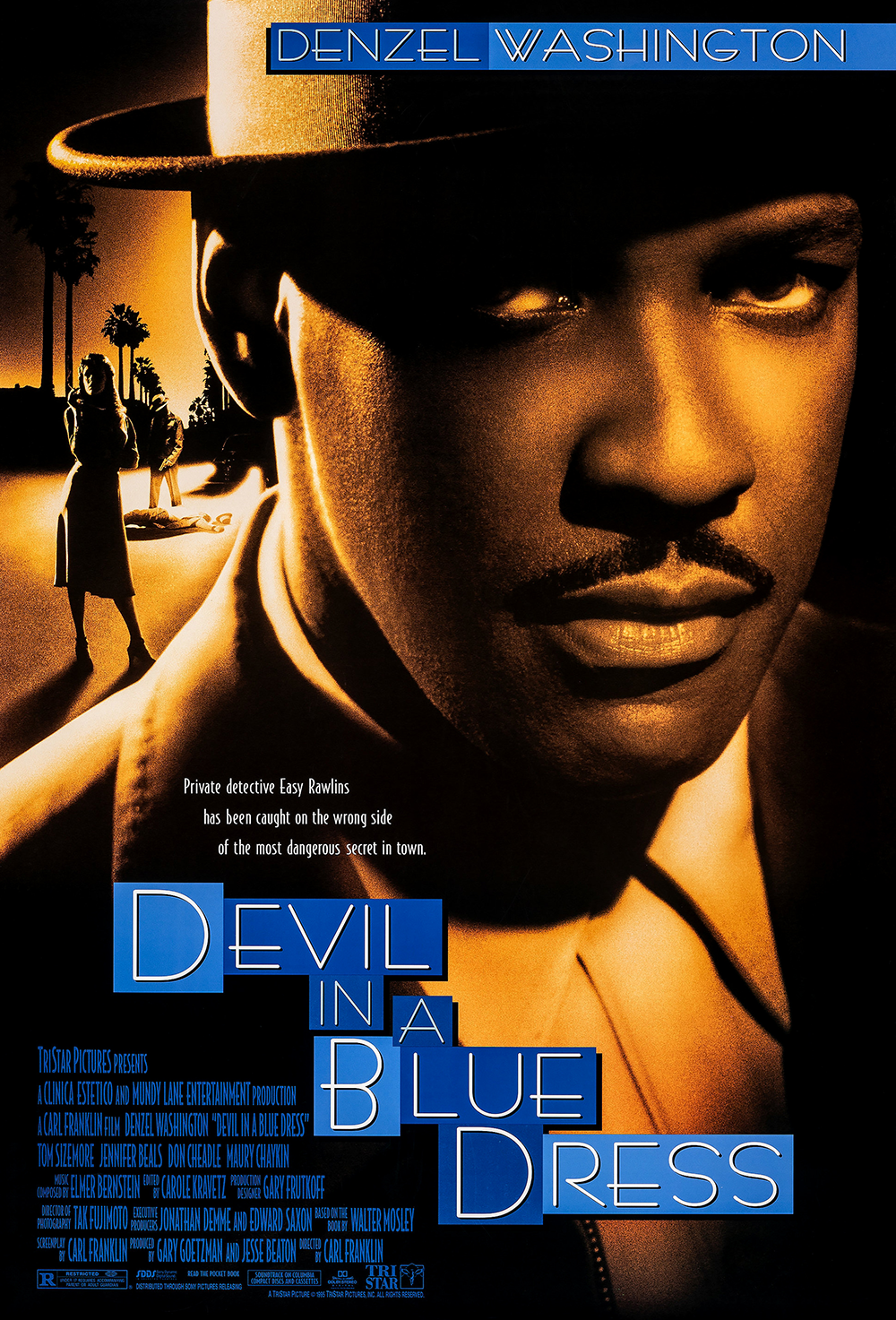

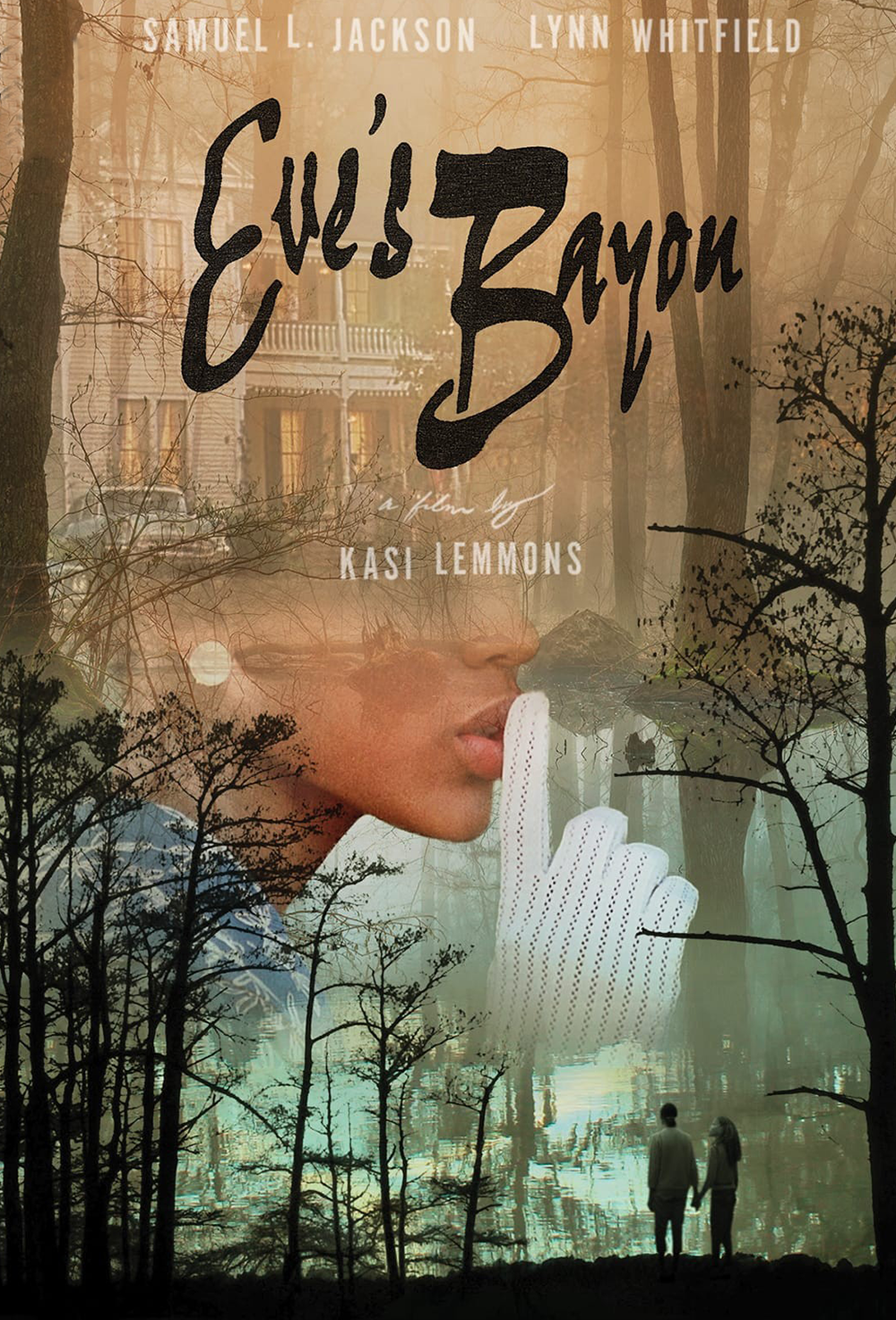

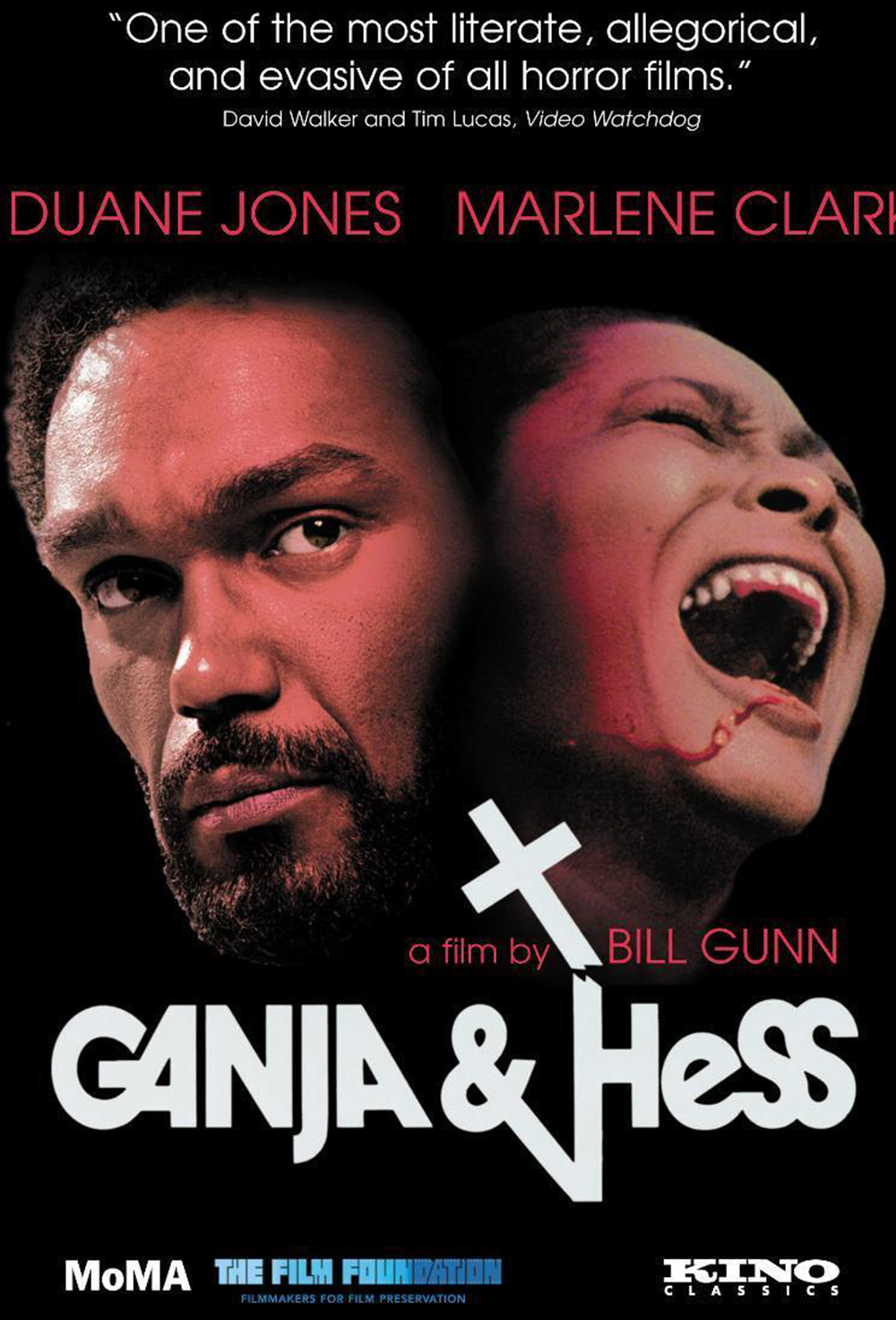

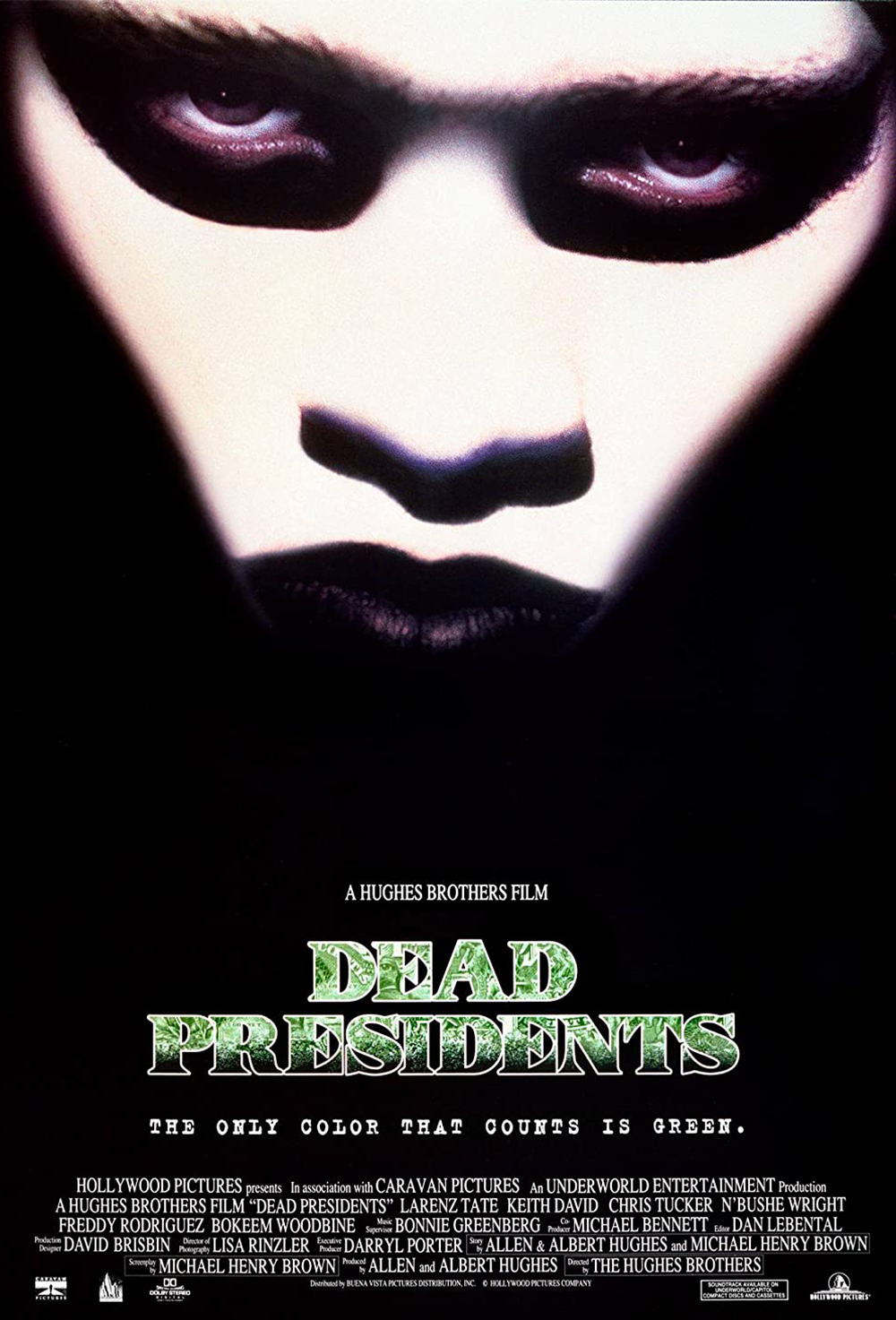

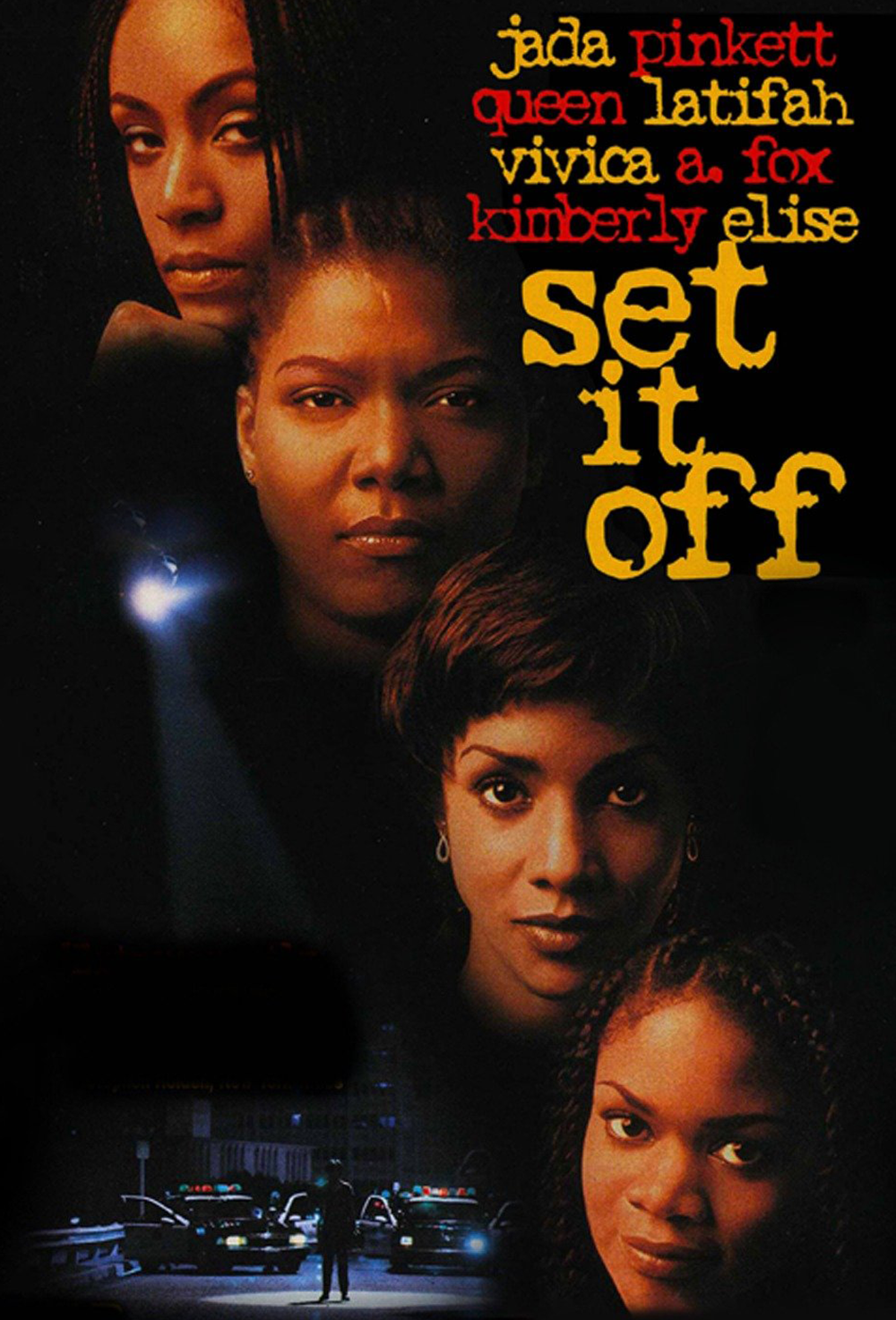

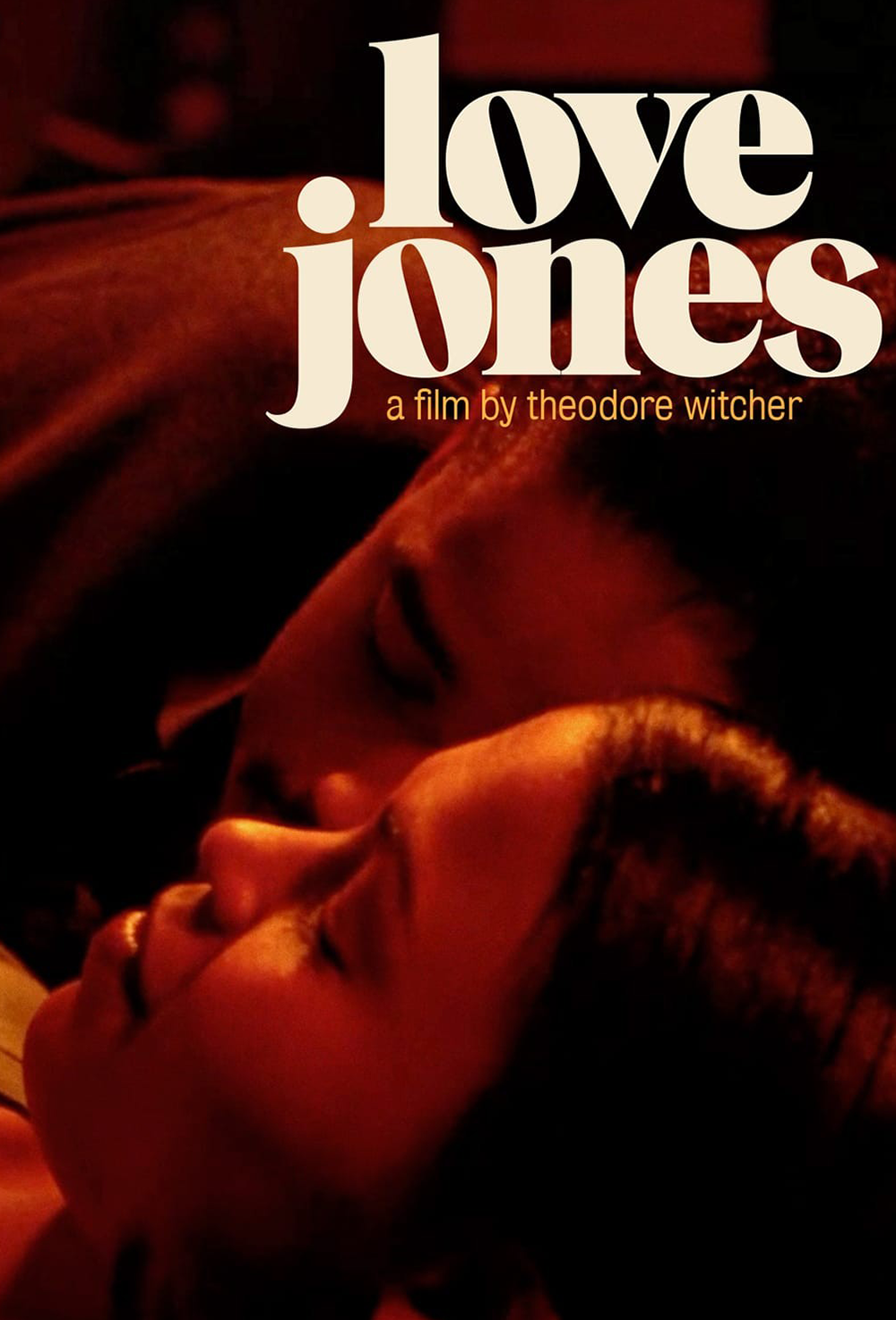

There are many hidden gems and likewise, many not-so-hidden gems in the Black cinematic canon that I highly recommend. I’m talking about work that speaks in the profound and crazy innovative voices of gifted auteurs, celebrates emotional truths through stories built around Black characters and showcases the jaw-dropping talent of Black performers. So much to choose from — whew! Here goes: Losing Ground (1982, dir. Kathleen Collins); A Soldier’s Story (1984, dir. Norman Jewison); One False Move (1992, dir. Carl Franklin); Devil in a Blue Dress (1995, dir. Carl Franklin); and Eve’s Bayou (1998, dir. Kasi Lemmons). Side note: yes, I’m a bit in love with the 90s! I need to add a few other critical titles: Ganja & Hess (1973, dir. Bill Gunn); My Brother’s Wedding (1983, dir. Charles Burnett); Dead Presidents (1995, dirs. Albert & Allen Hughes); Set It Off (1996, dir. F. Gary Gray); Love Jones (1997, dir Theodore Witcher). (It was impossible for me to limit it to five; I actually could easily add more!)

Lastly, I want to say a bit about the changing-yet-unchanging landscape that Black filmmakers are operating in. The nominations for the 2023 Oscars were recently announced and there were notable films by and about Black women that were very obviously shut out. Director Gina Prince-Bythewood issued a scathing statement to address this. She discussed the industry’s general retreat from the support for Black filmmakers that was so hot and heavy in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. During the pandemic, everyone was all about inclusion and elevating Black voices, and that has evaporated fairly quickly, like trends do. Prince-Bythewood also talked about the very real, very specific and very ongoing resistance to supporting Black women filmmakers and the stories of Black women. Her film, The Woman King, was excellent on every level — technically, structurally, artistically and in performance. What’s more, the box office and other metrics reflect that excellence; yet The Woman King wasn’t nominated for anything. Not one category. I think it was wonderful that a filmmaker of her stature spoke up in such a public way; even more wonderful, she also spoke on behalf of those Black women filmmakers who have yet to step on a set. This is me — when it comes to feature film. I have directed short films but my first feature film is now in development and it is becoming very clear to me what the landscape is and is not willing to offer. Racism in the film industry plays out systemically, culturally and individually. Nevertheless, I am very clear on why I do what I do — it is for my audience, of which I am a member. There are so many Black women, Black people, women of color, POC, who want and expect to see themselves centered onscreen, particularly in stories of the future; as well, there are white film goers who love good stories and who embrace inclusive storytelling because it is *reality*. I believe that a desperate commitment to patriarchy is the reason we continue to see an overrepresentation of white-male centric stories and perspectives (which includes simultaneously elevating yet objectifying white women at the expense of Black, Latina, Indigenous and Asian women). I want nothing to do with any of that. The toxic ubiquity of racist and misogynist dynamics in the 21st century disturbs me greatly, but it also makes me that much more determined to do what I do, the way I do it… with my eyes on the art.

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

APPLE TV

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

HULU

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

APPLE TV

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

TUBI

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

VUDU

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

HULU

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

AVAILABLE TO WATCH:

APPLE TV

AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

– Celia Peters

February 14, 2023